to take cover at the "first sight of a Yankee" to avoid being shelled. The streetcars to which he was referring were premotorized double-deck cars drawn by mules.

Eddie's mother had died when he was 4. In his autobiography, he lamented at his inability to remember her, "taking me on her knee, holding my little face between her hands, and pressing her loving lips to mine or tucking me into my little crib and kissing me good night -- as all mothers do." He was convinced she had done all those things but sadly he couldn't remember. The one memory he did have was his mother leading him into her room and spanking him with a slipper for some forgotten childhood misdeed.

Kells' father, Dr. Charles Kells Sr., was a family dentist who practiced his craft in the lower story of the three-story family home. As a teenager Eddie was incorporated into his dad's practice doing odd jobs. He "saw and heard a good deal more of dentistry than he would under other circumstances," he wrote. He matriculated at New York Dental College in 1876, graduating two years later -- the two-year curriculum being the norm at the time.

While in New York, he befriended several lab technicians at Thomas Edison's Menlo Park lab in New Jersey, spending considerable after-class time there. "Here I saw many interesting things in electrics, and, among other things, some of the first electric incandescent lamps [light bulbs]."

These experiences at the Wizard of Menlo Park's lab led him to a lifetime of tinkering and a fascination with the new age of electricity then in its infancy. "The tallow candles and oil lamps [of my youth] gave way to gas and then to electricity," he mused nostalgically two years before his death in 1928. He marveled too at how transportation had evolved during his lifetime "from sailing ships, to trains, subway and elevated 'electric cars,' steamships, cars and to cap the climax, by aeroplane and dirigible."

Page 1

By Daniel Demers, DrBicuspid.com contributing writer

Continued Page 2

Courtesy of:

November 12, 2013 -- In April of 1862, 6-year-old Charles Edmund "Eddie" Kells Jr. stood on New Orleans' Jackson Avenue pondering his impending doom. Union Adm. David Farragut had run his flotilla of 18 men of war up the Mississippi River into cannon shot range of the city. Union troops led by Gen. Benjamin Butler were on the outskirts of New Orleans poised to invade.

Young Eddie was eyeing the crushed oyster shells used as ballast between the streetcar tracks in front of his house in the old French Quarter of the city. Years later he wrote, "The word went around that Farragut would "shell the city." Kells youthful imagination envisioned union sailors "going through the city picking up those oyster shells and throwing them at everyone they saw." He vowed

Ouch ouch ouch: Profile of Dr. Charles Edmund Kells

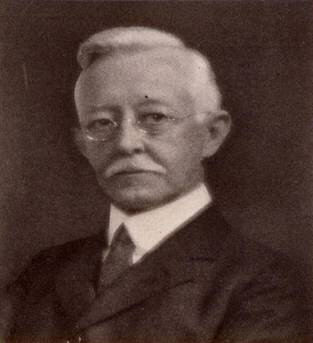

Charles Edmund Kells, DDS (1856-1928).

Kells returned to New Orleans in 1878, opening his own practice. He was destined to become one of the most famous dentists of his era, making major contributions to the profession. When he first entered practice, "there were no such animals as crowns and bridgework," no dental glues or cements, and "pivot teeth were mounted on single roots using a hickory dowel," he observed. Filling materials consisted of oxychlorid[e] of zinc, tin, gold, amalgam, and gutta-percha. In his autobiography, Three Score Years and Nine, he wrote that when he outfitted his first operating room in 1878, "there was very little to it. The chair operated by hand cranks, [an] old fashioned cuspidor, a Morrison foot engine [a foot pedal operated the drill], [a]cabinet and a washstand -- that's all there was." He noted that a

E-MAIL ME ddemers901@sonic.net